“Iwanu ga hana” is a Japanese proverb about wisdom. “Not-speaking is the flower” is its literal translation, while its meaning is that some things are better left unsaid or that ‘Silence is golden.’

In my mind, such proverbs and poetry condense imagery even as they put it under a microsope.

How the poetic image of “not-speaking is the flower” registers in our brains is an example of what many people find alluring about sayings from Japan and other Far Eastern countries, perhaps because such proverbs – along with the Japanese form of poetry known as ‘haiku’ – succeed in wrapping up image, awareness, and emotion in one spare bundle.

Japanese proverbs in particular may take the form of a short saying, an idiomatic phrase, or a four-character idiom. The Japanese are said to love proverbs and to use them frequently in their everyday speech.

However, instead of using the whole proverb, they often prefer to be brief and only use the first part of such well-known phrases. Using proverbs in this way enables the Japanese language to be compact, quick, and simple.

In addition, many Japanese proverbs are derived from agricultural customs, practices, and the outdoors because Japanese culture was traditionally connected to agriculture.

I have used one such proverb, i.e. “One kind word can warm three winter months” in this e-card:

This photograph was taken at a late autumn fair at a great estate here in England. My husband David and I had gone to the fair with one goal in mind which was to see its collection of owls as publicized. The owls were nowhere to be seen when we got there, however (we found out that their owner and trainer was called home because of a personal emergency and they went with her), so we turned our thoughts elsewhere.

It was a nippy, overcast day, the kind that runs straight to the bone. We were disappointed about the owls not being about when all of a sudden, our attention was drawn to the colorful paper fish that you can see in this e-card. They were attached to a rod outside a makeshift tent, twisting and turning in the sharp wind, and their vibrant colors cheered us up.

When I looked at David’s photograph of them some time later, the day came back to me: the almost bitter wind whipping through the site that afternoon, and the lone, bright kites who valiantly braved the elements that day.

Those kites remind me a lot of Japanese fish kites from that day I first saw them, hence my research for a fitting Japanese proverb.

I have also loved the delicacy of [Japanese] haiku for many years.

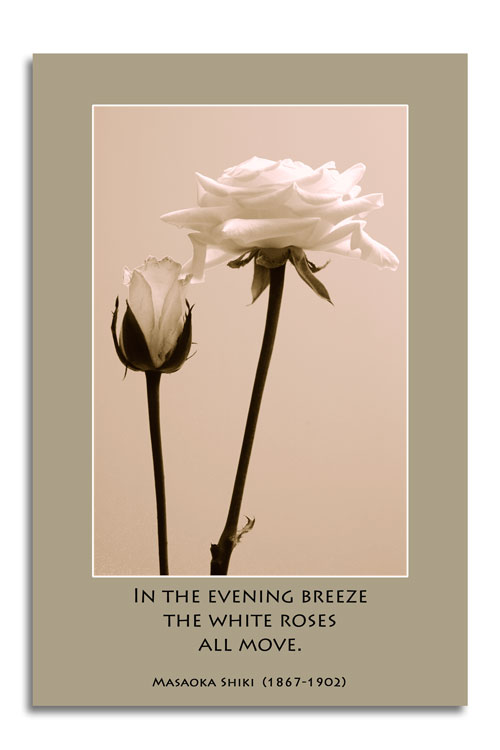

So when I came across another photograph of David’s consisting of two lone roses – one shorter, one taller – they reminded me of a couple, and I searched in my books for a haiku that would relay their simple, stark beauty.

This image is the photograph of the flowers, paired with a haiku by Masaoka Shikii that I found:

The Structure of Haiku

In the introduction to the book entitled “The Sound of Water: Haiku by Basho, Buson, Issa, and Other Poets” published in 2000 by Shambhala Publications, Sam Hamill who has translated the haiku in the text offers this explanation of what haiku is: “In three lines totalling seventeen syllables measuring 5-7-5, a great haiku presents – through imagery drawn from intensely careful observation – a web of associated ideas (renso) requiring an active mind on the part of the listener.”

An author of more than 40 books of poetry, essays, and translations from classical Chinese, Japanese, ancient Greek, Latin, and other languages, Hamill also claims that “the best haiku reflect an undeniable Zen influence. Elements of compassion, silence, and awareness of temporality often combine to reveal a sense of mystery.

Just as often, haiku may bring a startling insight into the ordinary… the poem is large enough – and sufficiently particular – to say it all. As is so often the case, the most important part is that which is left unstated.”

In Japanese, haiku are traditionally printed in a single vertical line, while haiku in English usually appear in three lines, as in the one above by Masaoka Shiki. These three lines parallel the three metrical phrases of Japanese haiku.

The Japanese writer Masaoka Shiki whose haiku I have quoted above about winter penned the name ‘haiku’ at the end of the 19th century.

It was previously called ‘hokku’ and popularized in the 1600s by the two master writers Matsuo Basho (1644–1694) and Ueshima Onitusura (1661–1738).

To contrast the haiku by Shiki about winter, I’ll end this with a hokku / haiku written by Basho that remind me of the beautiful springtimes that I experienced when I lived in South Korea:

From all these trees –

In salads, soups, everywhere –

Cherry blossoms fall