The Consequences of Breaking Off An Engagement in England

The idea of being sued in court for changing your mind after promising to marry someone may seem quaint today.

After all, couples break off their engagements or one jilts the other, and it is all put down to that mystery that is the human heart.

So it may come as a surprise to learn how recently the right to sue was taken off the statute books in England.

How It All Began

You might have thought that suing for breach of promise started in the Middle Ages. After all, that was when a man could ‘plight his troth’, which meant to vow the truth of his intention to marry.

In fact in the Middle Ages the only legal remedy available to someone who had been jilted was if they had given a gift to the other person ‘in contemplation of marriage’. If they had, then they could sue for the return of the gift.

Beyond that, breaking a promise to marry someone was a purely ecclesiastical matter and there were no financial consequences for breaking that promise.

The Role Of The Church

What the church could do was to ‘admonish’ someone who broke his or her promise to marry. Many of us will find it hard today to understand just what effect being admonished would have on a person or their reputation at a time when communities were much closer knit and everyone knew everyone’s business.

The Law Steps In

Then in the 1600s, in the reign of Charles I, the right to sue for breach of promise of marriage evolved in the ordinary common law courts.

It evolved in that peculiarly English way that most rights and remedies evolved, which was bit by bit, an inch at a time, with the courts trying at all times to avoid any hasty, sweeping principles that could trip up the judges and the courts at a later date.

As they evolved, breach of promise cases were treated like any other contract – that is, just like a contract to buy or sell cotton or potatoes.

If one party failed to honor his promise and broke the contract, the other could sue for damages for loss of the benefit that would have come from the contract had it been honored.

One interesting aspect of the fact that breach of promise was just like any other contract, was that in the same way that a merchant was not obliged to disclose all the faults and flaws in his goods, so the parties to an engagement did not owe one another any special duty to disclose all relevant facts.

So if one of them was hard of hearing, or penniless, he or she had no obligation to tell the other party.

It’s 1969

The year is 1969. The Beatles have finished their last public performance, which they played on the roof of Apple Records in London.

Neil Armstrong has walked on the moon.

And the Law Commission, charged in 1965 by the Engish parliament with reporting on things that ought to be changed in English law, have just reported on breach of promise in marriage.

Under a heading in the Law Commission’s First Programme that included “miscellaneous matters involving anomalies, obsolescent principles or archaic procedures” they singled out certain matters that, as they described it “seemed to rest on social assumptions which are no longer valid.”

In 1966 they started to circulate ideas and canvass opinions from lawyers and judges and from organizations that ranged from The Fawcett Society (which campaigns for equality between women and men in the UK on pay, pensions, poverty, justice and politics) to the Catholic Marriage Advisory Council.

The Law Commission published the results of their enquiries, and broadly, the lawyers wanted keep the statute and the other groups did not.

The Last One Hundred Years of Breach of Promise Cases

So what was the state of breach of promise over the 100 years before the Law Commission looked into it in 1966?

In the fifty years up to 1900 there were approximately one thousand breach of promise actions that ended in court with a trial with judgement and damages awarded by a jury.

More cases were started but settled before they got to court.

Until 1869 the court heard evidence from anyone and everyone except the parties themselves.

That was because until the law was changed in 1869, parties to a breach of promise action were forbidden from giving evidence in court.

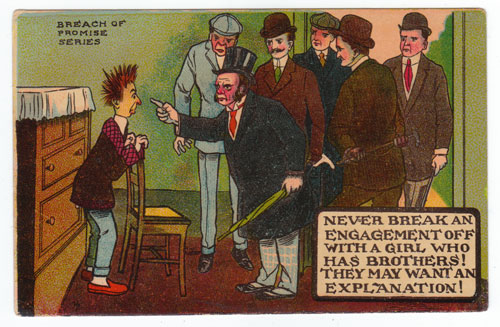

That did not stop the newspapers from printing the details of the evidence that was given by other witnesses, and breach of promise cases were a prime source of public entertainment.

They were so popular that several melodramas and comedies were written on the subject, centering on ‘the trial’.

In The Pickwick Papers, Charles Dickens wrote about poor misunderstood Mr Pickwick being sued for breach of promise by his housekeeper.

Women On A Pedestal Or Scheming Gold Diggers

In the breach of promise cases that came to trial, the defendants were nearly always men. And the lawyers for the defendants were usually reported as describing the women plaintiffs as scheming, avaricious gold-diggers.

The lawyers for the plaintiff women described the situation differently.

Women had very little economic independence. They could not work in many of the professions; they could not vote or be called for jury service.

So a woman who trusted a man and became engaged to him lost all chance of security if he jilted her. Her chance of finding a secure future was more or less ruined by now being cast-off.

In more than a quarter of the cases that came before the courts the parties had been intimate.

That presented the the all-male juries with a dilemma because the ideal of injured womanhood didn’t sit easily with the idea of a real flesh and blood woman having sex with the man who jilted her.

Nonetheless, unless the woman was proven to have loose morals she had a very good chance of success and the vast majority succeeded.

War and Change

Two World Wars changed the face of the country forever. Women had twice been recruited for essential war work while the men were off being blasted to bits for King and Country.

By the 1950s the number of cases was reduced to a trickle, and by the time the Law Commission reported, breach of promise was obsolete.

The law abolishing it was passed in parliament in 1970 and became law in 1971, and when breach of promise came to an end it did so in a world that was very different from the one in which it began.

The Act that abolished the action for breach of promise is the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1970 – a short Act of just seven paragraphs and one schedule.

The Act preserved certain rights over property, and those rights continue to this day. If you think this situation might affect you, ask a lawyer.

References

The Law Commission Report Vol 26 October 14, 1969

‘Promises Broken: Courtship, Class, and Gender in Victorian England’ G.S. Frost Virginia Press 1995

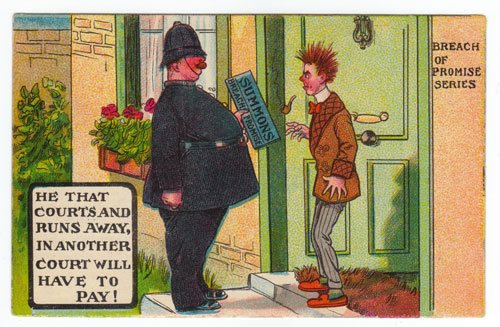

Postcard images: Printed in Germany for the English market in the 1930s