My favorite British English idiom is It’s no use flogging a dead horse. If you are not familiar with the idiom, it means it’s no use trying to accomplish that which cannot be accomplished.

I read somewhere (I think it was in a Philip K. Dick novel) that one of the hallmarks of schizophrenics is that they take idioms literally and don’t see beyond them to the symbolic or figurative meanings.

In other words, flogging dead horses for them is only about flogging dead horses. Perhaps it is even only about flogging the particular dead horse that is being referred to.

I wonder whether people who suffer like this imagine some scenario with the event occurring in their mind’s eye – perhaps a London street in the 1930s with a man flogging his horse that lies dead in the road, still bound into the shafts of the cart?

Whether what is said about schizophrenics is true or not, it does illustrate that phrases open virtual, symbolic worlds that must be understood if the idioms are to be understood.

Another idiom I like for its four pithy words that speak volumes, is Clothes maketh the man. One cannot imagine that the idea behind the idiom could have been expressed through people adopting, for example, the words ‘Onions maketh the man’.

But there are a number of phrases or idioms where you have to wonder how they originated and why they gained ascendance when others that were perfectly suited did not.

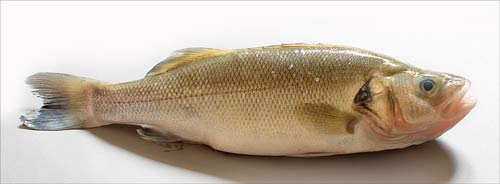

For example, why do we say That’s a different kettle of fish – meaning that’s a completely different matter from the one previously mentioned?

And why do we use its near-relative That’s a pretty kettle of fish – meaning a difficult predicament?

It is true that a kettle, or at least a ‘fish kettle’, is used for cooking fish. If you haven’t come across a fish kettle, it is a vaguely fish-shaped pan with a lid. So a ‘kettle’ makes sense in relation to the fish in the idiom, but why a kettle at all, and why a fish?

Why not a different basket of onions? Why not a different grove of trees? Why not a different breed of dog?

And getting back to onions, how did He knows his onions – meaning that he has an extensive knowledge of the subject matter – come to be chosen over, for example ‘He knows his geologic time scales’.

And why do we say Don’t badger me? It’s true that badgers were baited by dogs, but then so were bears – so how did badgers come to claim the territory?

Wouldn’t it be interesting to go back in time and see the first utterance of Don’t badger me and follow it down through the course of history. Who knows, perhaps we would see someone offer up Don’t bear me as an alternative, only to be ignored while the badger gained the ascendence.